About Her: textile artist Anni Albers

Image Source: The Thread

“Besides surface qualities, such as rough and smooth, dull and shiny, hard and soft, textiles also includes colour, and, as the dominating element, texture, which is the result of the construction of weaves. Like any craft it may end in producing useful objects, or it may rise to the level of art.”

— Anni Albers, On Designing

Anni Albers redefined what weaving could be: elevating it from “women’s work” to an experimental, expressive, and architectural medium. She is credited with blurring the lines between traditional craft and art — she wove language, history, and cultural references into her work, liberating weaving from its social constructs and turning it into an art form. As both a pioneering textile artist and an influential educator, Albers played a central role in shaping modern art and design. Yet, like many women of her era, her significance was often sidelined in broader design histories. Her work and style can still be seen echoed in modern textiles and fabrics today. This month, we revisit three of her key works and explore how she wove structure, meaning, and modernity into fabric.

Born Annelise Fleischmann in Berlin in 1899, Anni Albers was raised in a wealthy and artistic Jewish household. Her father was a furniture manufacturer; her mother came from the Ullstein family, proprietors of what was then Germany’s largest publishing empire. Immersed in a world of art and design from an early age, Albers’ childhood was filled with orchestral performances, elaborate costume parties, and private figure drawing lessons—all of which laid the groundwork for her lifelong creative pursuits.

As a young adult in 1922 she enrolled in the Bauhaus, initially aspiring to become a painter. At the time, women students were unfairly restricted from disciplines like architecture or fine art and were often funneled into the weaving workshop. What began as a gendered constraint became the foundation of Albers’s lifelong practice. Whilst at the Bauhaus, Anni met the artist Josef Albers, who she later married in 1925.

Image Source: CWHF

By the early 1930s they both worked as a part of the Bauhaus faculty and elected the school to be closed rather than to comply with the looming third Reich. This was an unsettling time for the couple, who lost their jobs and feared for Anni’s life as a jewish woman in Germany. By 1933 the Albers were granted the ability to emigrate to the US, after architect Philip Johnson (an admirer of Anni’s work) offered the couple the opportunity to work at the Black Mountain College in North Carolina.

In 1949, Anni became the first textile artist to have a solo exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art in New York, a major breakthrough that helped reframe weaving and textiles as a medium worthy of serious attention – no longer just a craft, but a serious art form.

The show marked a turning point in her career, bringing wider recognition for developing an approach to weaving that was both technically rigorous and aesthetically radical. Albers was approached by Florence Knoll to design textiles for the Knoll furniture company. For the next thirty years she worked on mass-producible fabric patterns, focussing especially on her pictorial weavings, some of which are still available today. In the decades that followed, Albers wrote and taught extensively, publishing On Weaving in 1965, a text that remains essential reading for designers and makers. In the later decades of her life, Albers finally began to receive the recognition she had long earned.

Image Source: R&Company

In 1976, she was the subject of two major exhibitions in Germany, followed by a series of shows focused on her design work over the next twenty years. During this time, she received numerous lifetime achievement awards and six honorary doctorates — including the American Craft Council’s Gold Medal for "uncompromising excellence" in 1981. More recently, in 2018, the Tate Modern and the Kunstsammlung Nordrhein-Westfalen in Düsseldorf staged a landmark retrospective of her work — a long-overdue celebration of a life woven through modern design history.

After Josef’s death in 1976, Anni continued to work, travel, and exhibit internationally until her death in 1994. Her commercial work is still available via Knoll: (https://www.maharam.com/products/eclat-weave-by-anni-albers-1974/colors/003-pine)

If you’d like to dive deeper on her textiles, this excellent archive offers a look at Albers’ extraordinary range of textile work — bold, experimental, and as modern today as it was then: https://lindsayrgwatt.com/moma/artists/96/anni-albers/

And this recent collaboration with Loewe is a great watch: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JVajwPAfRRs

Image Source: Public Delivery

Project one: Wall Hanging (1926)

Image Source: MoMA

The subtle rhythm of pattern and colour reflects the Bauhaus emphasis on merging craft and modern industry. Whilst the original is housed in the collection of The Museum of Modern Art, Wall Hanging has been reimagined as prints and rugs, see more here: https://christopherfarr.com/rug/design-for-wallhanging-1926/

Image Source: Christopher Farr

Project two: Bedspread Material for Harvard Graduate Center Dormitory (1949)

In the late 1940s, Harvard — like many American universities — was suddenly full again. Veterans were returning from the war, many for the first time in years stepping into quiet routines of study and shared housing. To meet the demand, the university commissioned its first Graduate Center from fellow Bauhaus alumn Walter Gropius: a sleek modernist complex that traded ivy and ornament for glass, steel, and a new kind of future.

Inside these rational, postwar buildings, Gropius commissioned a number of ex-Bauhaus friends who had recently immigrated to the USA. Albers was asked to design the bedspreads and textiles for the room-dividing curtains for student rooms, amongst other more high-art installations.

Image Source: MoMA

Although for the first time in the university's history Gropius had insisted upon a set budget for custom textiles, that budget was not generous. Gropius wanted something durable and affordable; Albers felt depth, colour, and feeling were of priority. Their compromise was cotton, woven into three saturated plaid patterns: hardwearing enough for daily student life, but rich enough to lend warmth to an otherwise restrained space.

Image Source: Harvard Magazine

It’s the kind of design moment we love: quiet, considered, and entirely human. A simple thing — a bedspread — but in Albers’ hands, a reminder that even the most functional objects can hold warmth, memory, and meaning.

Image Source: MoMA

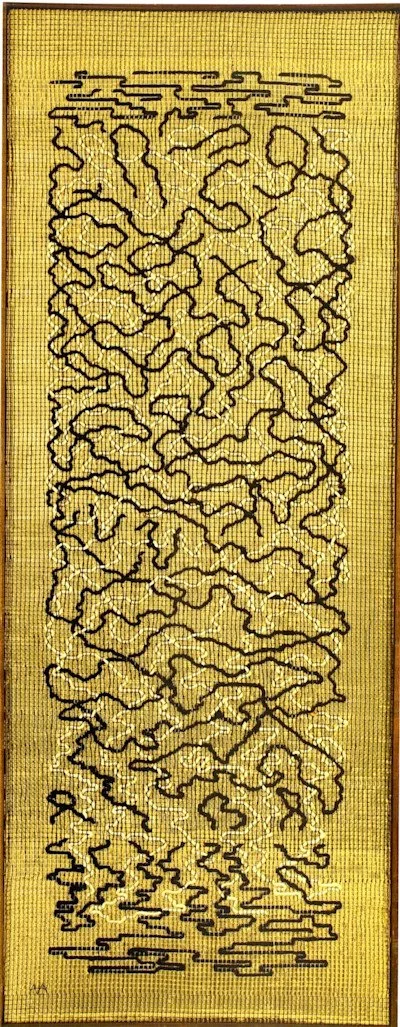

Project three: Epitaph (1968)

Made later in her career, Epitaph is both a technical and emotional achievement. A jacquard-woven textile that integrates synthetic and natural fibers, it’s one of her most poetic works. Throughout her career she utlised non-traditional materials jute, paper, horse hair, and cellophane in her weaving. In the early 1940s, when Albers’ new classroom at the Connecticut was still without looms, she sent her students outside to collect their own weaving materials from nature, while imagining the ingenuity of ancient weavers who worked without a supplier catalogue. This mixture of what is available and what is man made or at hand has resulted in works with incredible texture and depth like Epitaph. The monochrome palette and quiet geometry suggest solemnity, yet the shifting rhythm of the composition feels alive. The title invites personal and historical readings—possibly a tribute, a farewell, or a reflection on loss and legacy.

It exemplifies Albers’s unique ability to balance abstraction and intimacy, transforming thread into narrative. While Epitaph could be read as an endnote, it is more accurately a summation of Albers’s lifelong philosophy: that weaving is a language—tactile, precise, and profoundly human.

Image Source: Hali